John W. Morris

The point was, though, it was the right thing to do. After all, the city of Seattle was another

government within the United States spending federal dollars and needing help. The Corps

was available, had the capability, and would be paid for its service. Finally, the Corps helped

Seattle. It was not a great deal of effort but it was enough to solve the need. That began the

whole idea that we should probably make the Corps' capability, through its labs and

otherwise, available to others under selected conditions.

We've done work for the Department of the Interior, including the Bureau of Reclamation.

I think it was either General Hatch or General Heiberg along with General Wall who preached

the idea of the "federal engineer. That's the concept. I think it's a little stretch and risks some

resentment to say, "The Corps will be the federal engineer," but the idea is right. The more

work you do for others and do it well, the more likely you are to get there by evolution rather

than by dictum. If you put up on the table the thought that the Corps is going to be the federal

engineer, you would probably get a lot of competition and argument about it. If you get there

by growth, you'll probably make it because the Corps can do all these things and do them

well. The Congress recognizes that and always has. That's how the Corps grew in the water

business in the first place.

So I think the work done for others is more than just the work itself, it's a whole philosophy.

It's necessary for the survival of the Corps. In the 1970s we could see the construction work

going down and the operation and maintenance going up, but in order to keep our tools sharp

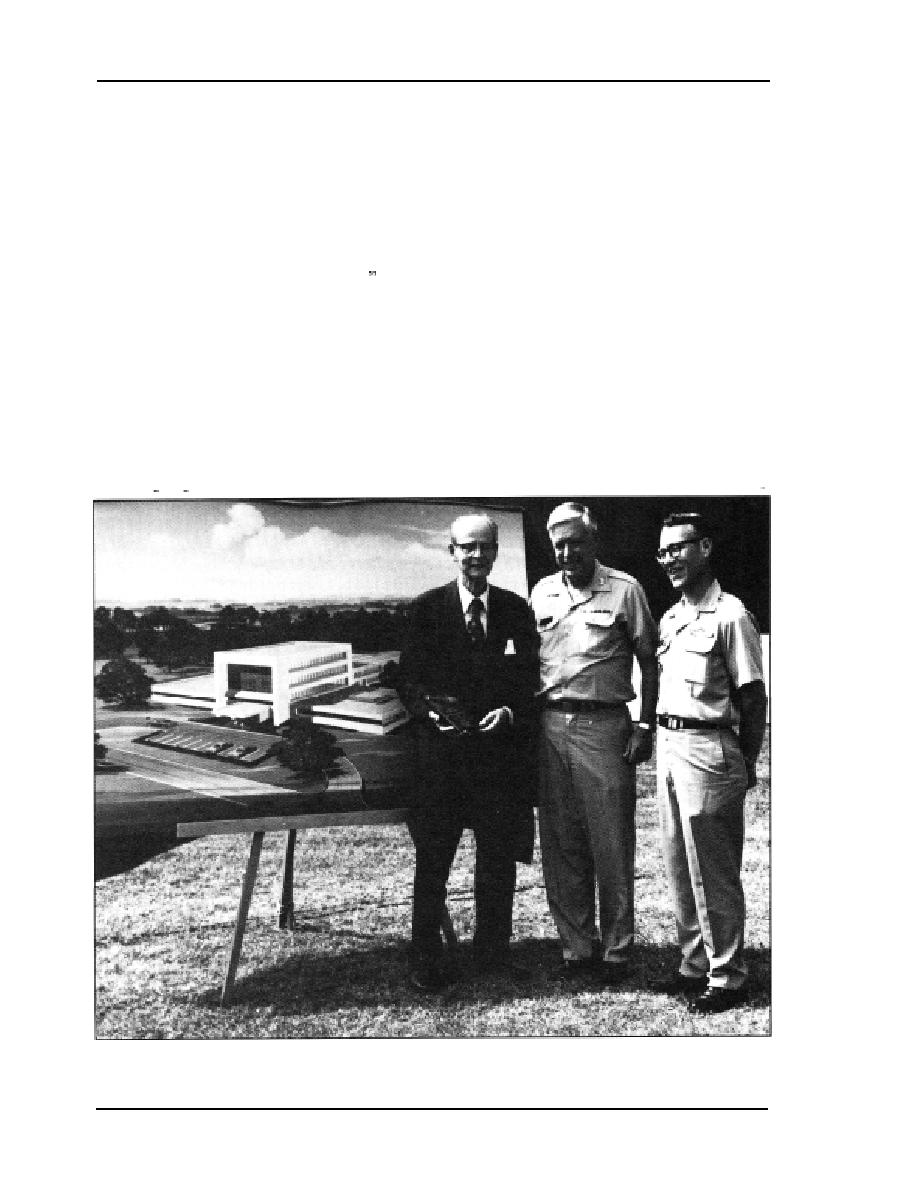

Groundbreaking ceremony of the Arthur Casagrande Building at the Waterways Experiment

Station in Vicksburg, Mississippi, on 28 June 1978. Next to the prominent engineer, Casagrande

(left), are General Morris (center) and Colonel John L. Cannon, commander and director of WES.

163

Previous Page

Previous Page