Defending America's Coasts, 1775-1950

Meanwhile, weapons technology was rendering these fortifications obsolete. During the Civil War,

heavy rifled guns with newly developed ammunition partially reduced Fort Sumter, South Carolina,

and Fort Pulaski, Georgia, to rubble. At Fort Sumter, the Confederate defenders piled earth and sand

before and behind the masonry walls, making the fort impervious to enemy shelling. As a result, both

Union and Confederate engineers began erecting earthen coastal forts and batteries, generally

forsaking the old masonry

In addition, the Civil War saw the use of the

underwater mine as a supplementary coast defense

measure. The Confederacy, without a large navy to

protect its harbors and rivers, used submarine

mines-often called torpedoes-to protect its

waters from attacks by Union ships. Matthew

Fontaine Maury, first chief of the Confederate

Torpedo Bureau, used mostly contact mines, which

exploded upon impact with a vessel, but

experimented with other types. This defensive

measure inspired David G.

statement, "Damn the torpedoes, full steam ahead,"

uttered during his attack at Mobile

Although the Corps of Engineers maintained many

of the masonry forts after the Civil War, it

constructed a number of earthen batteries as

primary structures in the

Actually, in light of

Civil War experience, the Engineers were in a

quandary over the kind of defenses needed. They

were sure, however, of the need for a practical

submarine

In 1866, Congress abrogated the Corps of

Engineers' supervision of the U.S. Military

Academy at West Point. The Corps established its

new home at Fort

in New York Harbor,

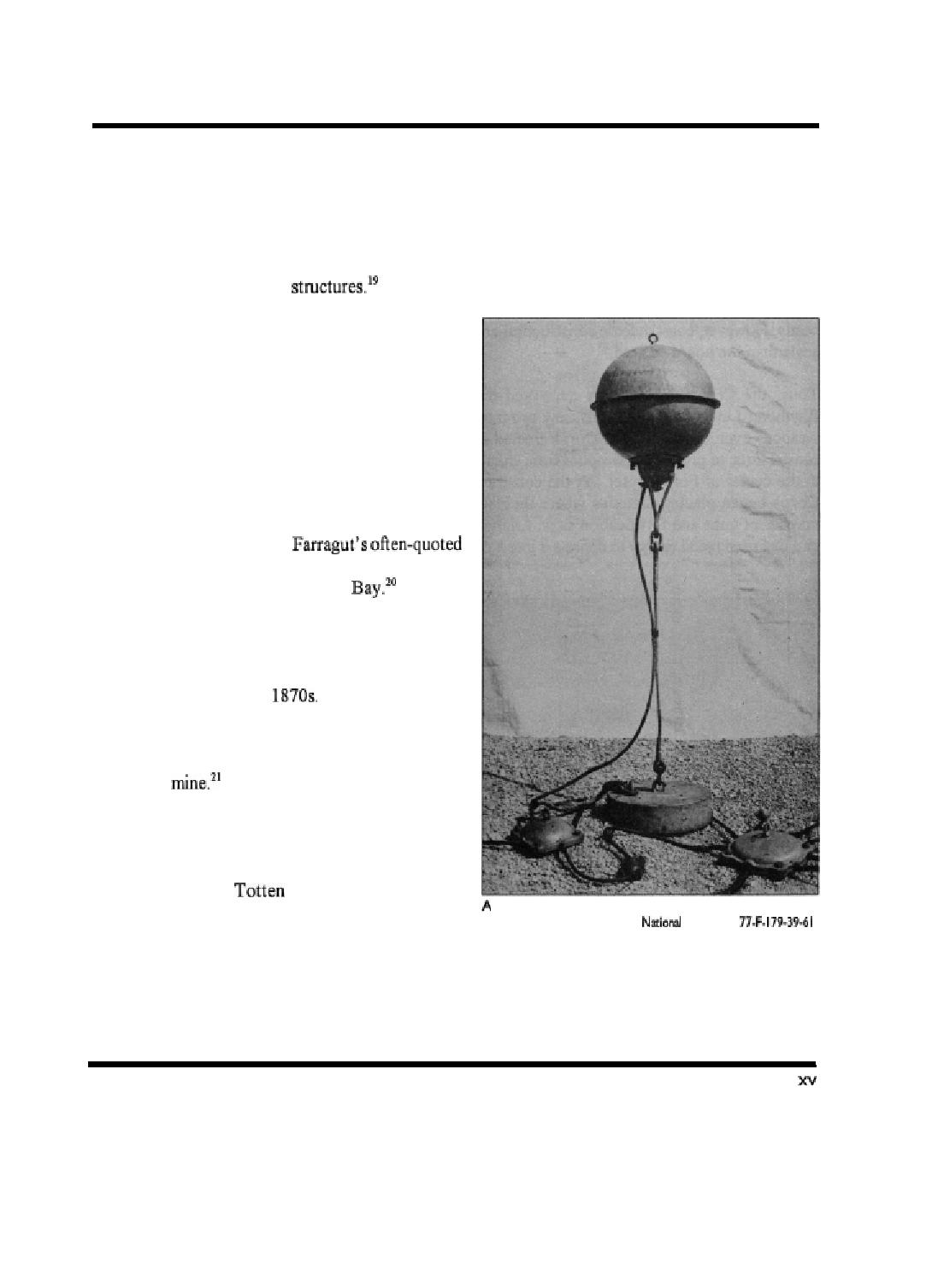

buoyant torpedo (submarine mine) and connections.

where it created an Engineer School of Application.

Archives,

Some of the school's staff, especially Major Henry

Larcom Abbot, began experimenting with

submarine mines. Disregarding contact mines, they attempted to develop a reliable electrically

detonated device. As an outgrowth of this work, the War Department established the School of

Previous Page

Previous Page